And he was, by most accounts, wrong about just about everything.

Of course, being wrong about just about everything in the mid 1600s wasn't terribly uncommon. Everyone "knew" plenty of things, but those things turned out to be quite wrong. But yet, despite it all, Kircher laid more foundations than he ever could have imagined, and many of those foundations were responsible for new discoveries, or expanded knowledge. In a way, it's almost unbelievable how he could be so wrong, yet be responsible (even indirectly) for people discovering the truth. To say nothing of the numerous things that he was so close on, but still short the mark.

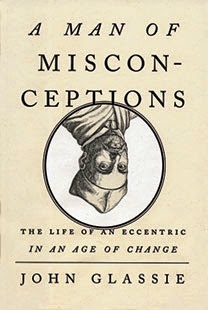

A Man of Misconceptions is a rather engaging biography of Father Kircher, reaching back to his boyhood and projecting forward, beyond his death. It takes heavily from contemporary accounts, biographies of other greats of the time, letters and works from his contemporaries, as well as Kircher's own autobiography.

It has a somewhat lighthearted tone, not taking itself too seriously, probably because of Kircher's own somewhat dry wit. For instance, Kircher's comments on a personal setback in the form of domestic turmoil related to the 30 Years War: "a new crisis arose which presented to me the ultimate occasion to endure suffering and grief on behalf of Christ."

I can't say the book gave me new appreciation of Kircher, as I hadn't really heard of him until I read it. However, it did paint the story of a fascinating man. While he believed in the prevailing miasma theory of disease ("noxious vapors" cause sickness), he also believed that it was spread by "minute worms" that spawned in the noxious vapors. So, he was wrong about vapors, and wrong about worms (there's no way his primitive microscope could have seen the bacteria responsible for Bubonic), he was right about the disease being cause by living creatures; 200 years before Pasteur. Likewise, he did extensive "translations" of Egyptian hieroglyphics. He was completely and utterly wrong about every single translation he did. Yet he laid the groundwork for the connections between hieroglyphics and the Coptic language. His ideas on geology, volcanoes, and ocean currents were hampered by the wisdom of the time (such as metals "curing" and turning into gold) and the lack of knowledge of tectonic plates, but he was in the right ballpark. For all his inaccuracies, he was almost always in the ballpark.

I can see why he's something of a poster child for post-modernist thinkers. His beliefs fit in perfectly with the accepted wisdom at the time, but were never-the-less wrong. I can see the attraction of drawing lines between Kircher and modern science. I certainly wouldn't go that far, but I could certainly see him as someone to point to when getting to cocky.

I find myself wondering what Kircher would think if he was dropped into the 21st century. Aside from "stunned", I think he would be equal parts delighted and horrified. Finding out he was almost universally wrong would certainly sting the ego. On the other hand, I can see him staring in awe at the information available via the internet. And he'd probably wonder what the Hell is wrong with everybody in using such a glorious tool as a means of sharing pictures of cats.

No comments:

Post a Comment